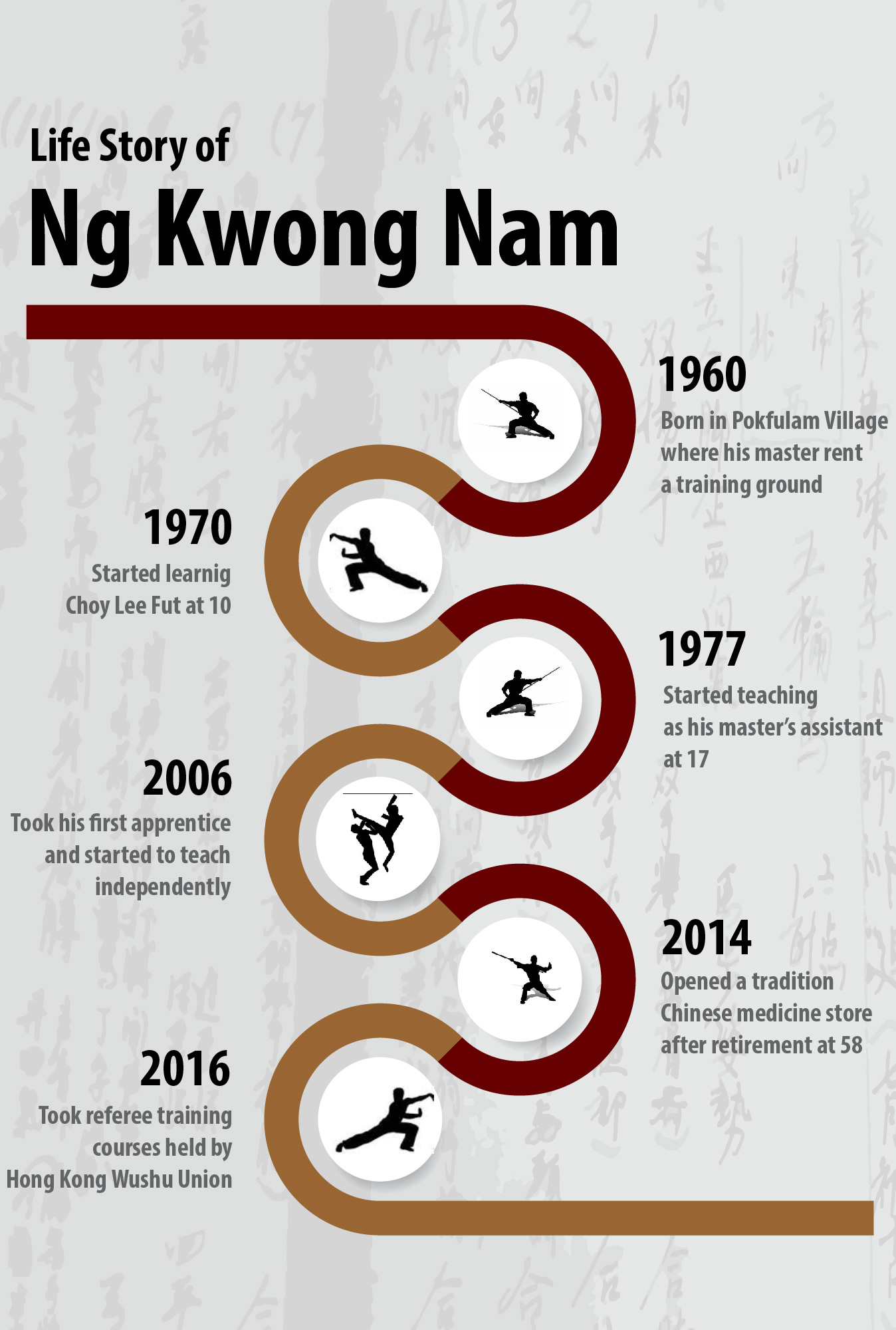

Ng Kwung Nam, the 57-year-old kung fu master, walked into the world of Choy Lee Fut because of 10 dollars.

That was in 1970, just after Ng was accepted by a Choy Lee Fut master as an apprentice. A police officer dropped by at his master’s place for dinner one day, and asked kids at the training ground to perform. Though not that skilled yet, Ng joined the group and practiced some moves he learnt in the morning. He ended up getting a red pocket with 10 dollars from the officer, which meant a lot for a kid in those days.

“The whole village was amazed!” Ng says and laughs.

From then on, he has spent more than 40 years performing Choy Lee Fut, and becomes a living witness of all the ups and downs in his master’s life. After government took back the training ground that his master rented, they moved to the rooftop of a tea house. Then Wing Hing Building near Sai Wan market, and then its rooftop again. Their long journey of moving to another training place finally ended as the master could not afford one anymore.

Among 20 fellow apprentices with whom Ng was trained, he is the only one still making Chinese medicine, performing Choy Lee Fut, and teaching dragon and lion dance.

Ng remembers how amazed he was when he went back to Xinhui city, the birthplace of Choy Lee Fut, to participate a contest in 2016.

Hundreds of children at martial arts school rushed into the playground, training and performing in white garments, with their masters standing on the stage to supervise. “In Hong Kong you can’t even find a hundred people to eat together. Not to say learning martial arts!”

Ng was never that lucky as a master. Starting to teach as his master’s assistant at the age of 17, he has only taken about 20 apprentices in the past 40 years, to whom he passed on not only Choy Lee Fut but also dragon and lion dance and sword playing.

Several generations before, it is a tradition for kung fu masters to hide their best and most unique moves from apprentices, but all Ng does now is the opposite – to pass on Choy Lee Fut culture as intact as possible. He gives away all the once secret diagram books, though they are not useful anymore because “anyone can record your moves by a cell phone.”

“I get a sense of satisfaction every time a protege finishes training. Great apprentice means great master, it’s the same,” Ng says.

Time has changed, and so as traditions and ideas from the past.

“We were like frogs in the well, listening to everything told by our masters and knowing nothing about world outside.” When Ng was a kid, training was the most exciting part in everyday life, while his apprentices are faced much more distractions. “Kids now have phones and TV; you can’t expect them to stay focused like we used to be.”

There are, however, traditions from the past that Ng is unwilling to change.

In Hong Kong, very few masters can earn a living simply by teaching and performing kung fu. Ng was a car driver before retirement, after which he opened a traditional medicine clinic in Sai Wan.

Likewise, his master also worked as a full-time doctor at Queen Mary Hospital before he retired and started a martial arts centre, spending all his savings on rent of training place.

But as kung fu becomes a globally renowned icon of Chinese culture, some from this profession find a much easier way to make money – to mass produce kung fu diagram books, and to organize crash courses that take only several hours for an outsider to learn all the moves.

Ng thinks the idea of commercializing kung fu is simply “wrong”, because it breaks traditional master-apprentice relationship, in which very rare does an apprentice switch his master.

“What they do is basically selling traditional culture,” Ng says, shaking his head. “You can say that I’m conservative or stubborn, but I don’t want to go that far.”

“Choi Li Fut is not a tool for survival for me.” And hopefully, this is a tradition that time will not change.